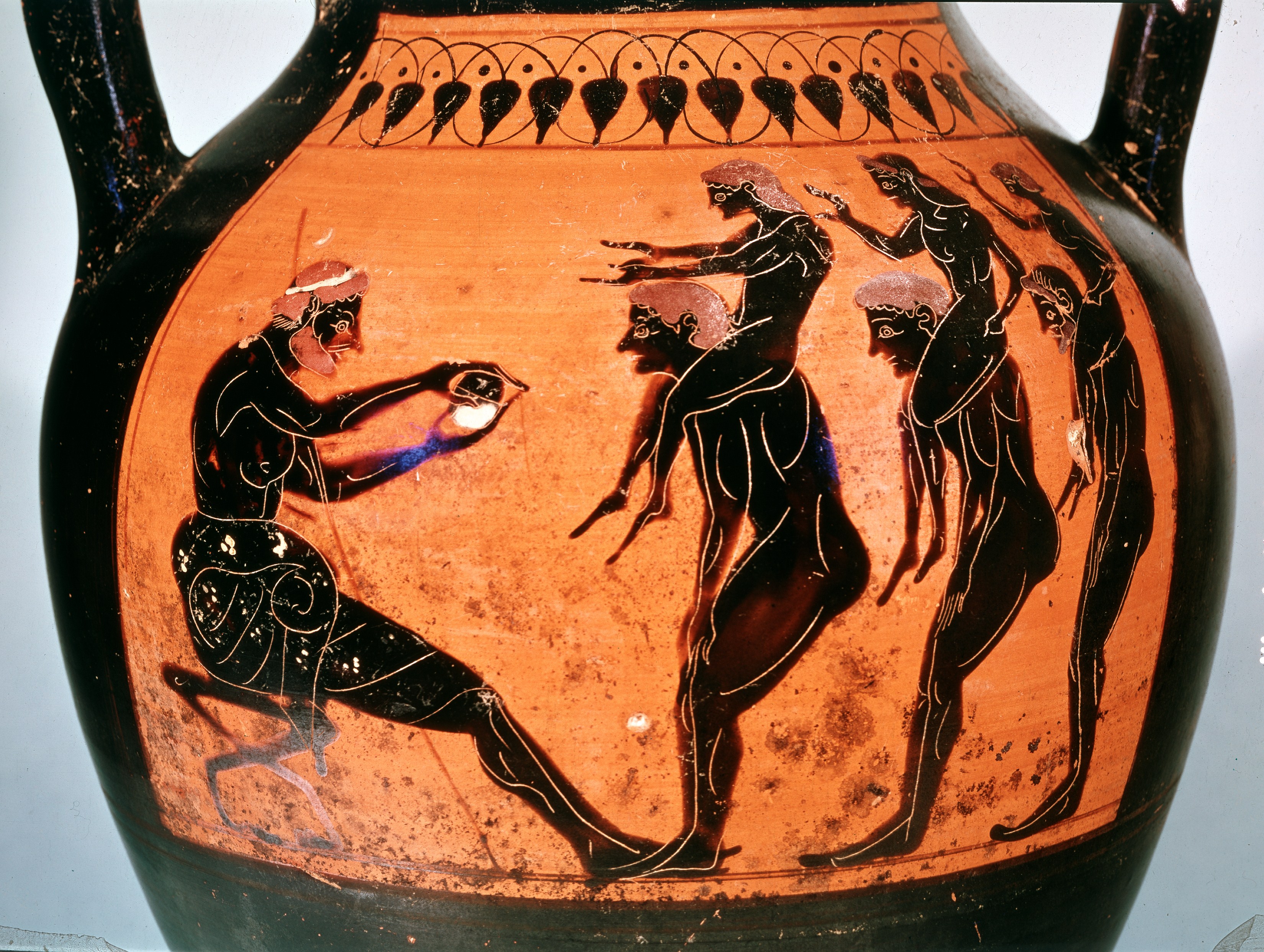

- Red-figured amphora, Greek, made in Athens, 510–500 BC, Attributed to the Dikaios painter, from Vulci, Italy, GR 1843, 1103.41 (Vase E255) AN 367073001, © The Trustees of the British Museum (2013). All rights reserved.

- Athens

I have worked on many big, exciting exhibitions at the DMA since I came here in 1975, ranging from Pompeii AD 79 to Chola Bronzes from South India, Splendors of China’s Forbidden City, and Tutankhamun: The Golden Age of the Pharaohs, but The Body Beautiful in Ancient Greece: Masterworks from the British Museum is one of the most extraordinary. On my many visits to London, I am always amazed at the treasures in the British Museum, and now Dallas has a chance to see some of their best art at the DMA.

- Olympia

- Delphi

I still remember my first trip to Greece in 1960. My husband, Alan, and I roamed, sometimes as the sole visitors, over the acropolis in Athens, the AcroCorinth Mountain looming over the ancient city of Corinth, the temple of Apollo at Delphi, with its precipitous view straight down a mountainside to the sea, and the ruins of Olympia, where the Olympic Games began. No one was at Olympia then, except a boy herding black goats and someone playing a flute. Otherwise, the wind blew over the grasses and fallen stones. It was like visiting Pan, the god of nature, on his own turf. I fell in love with great sculptures like the youthful Charioteer at Delphi and the majestic Poseidon in Athens, feeling for the first time the stunning impact of ideal human beauty envisioned in art. Some of Alan’s photos from our trips to Greece will be part of an educational video on the sites of the Panhellenic games.

Marble statue of a victorious athlete, Roman period, 1st century AD, after a lost Greek original of about 430 BC, © The Trustees of the British Museum (2013). All rights reserved.

The Body Beautiful in Ancient Greece: Masterworks from the British Museum displays this Greek vision of ideal human figures, particularly male nude figures. Such sculptures were admired by the Greeks because they believed that a young man who was a victor in one of the great athletic games, and who performed naked, had reached the height of glory that a man could achieve. Such victories were akin to dying heroically in battle. The same vision is best expressed in literature in Homer’s Iliad, where Achilles leads the Greeks to victory over Troy, but dies before the war is over. This ideal of human triumph is expressed in several works in the exhibition, particularly the discus thrower by Myron and the young athlete by Polykleitos. Although both of these works are shown in later Roman versions, they embody the Greek ideal of a radiant youthful victor. In a way the figures look ideal and “classical,” and in another way they are very seductive. They remind me of Keats’ description of Greek figures in Ode to a Grecian Urn: “Forever warm and still to be enjoyed; forever panting and forever young.”

Marble statue of discus thrower (diskobolos), Roman period, 2nd century AD, after a lost Greek original of about 450–440 BC, © The Trustees of the British Museum (2013). All rights reserved.

Works like the discus thrower and several other pieces in the show come from the great villa of the Emperor Hadrian at Tivoli, built in the 2nd century AD. They are testaments to the influence and vitality of Greek art during the Roman Empire. Hadrian was a very cultivated man who collected Greek art and commissioned many artworks in the Greek tradition. He was also personally a lover of young men. His character and life are well described in Marguerite Yourcenar’s novel Hadrian’s Memoirs. Hadrian’s villa is another delightful place that Alan and I visit often: it is a gorgeous temple of art and landscaping.

Black-figured amphora, Greek, made in Athens, about 540-520 BC, attributed to the Swing Painter, probably from Etruria, Italy, © The Trustees of the British Museum (2013). All rights reserved.

Besides the marble and bronze sculptures, the exhibition includes numerous painted vases, which bring to life the kinds of sports performed at Greek athletic competitions, stories, and myths of gods and heroes, and many scenes of ordinary life, including erotic encounters. Alan and I have collected ceramics all our lives, including some Greek examples. Greek vase painting has a narrative appeal; many images suggest the dramatic scenes found in the Greek theater, as well as actual scenes of masked actors. The love of real life and people is as important in Greek culture as idealizing art. I always think that it’s important to remember that the Greeks were keen observers. The kind of study of living bodies that you see in Greek sculptures is similar to the understanding that led to advances in science and medicine.

Bronze statue of Zeus, Roman period, 1st century AD, after a Greek original of about 440 BC, said to be from Greece, © The Trustees of the British Museum (2013). All rights reserved.

One of the most significant figures in The Body Beautiful in Ancient Greece is Herakles, a human hero, but also the child of Zeus, king of the gods. Herakles accomplished superhuman labors triumphantly (such as killing the Nemean lion, whose skin he is shown wearing), but he also suffered greatly. Driven mad by the jealous goddess Hera, he killed his first wife and children. At the end of his life, he was poisoned in ignorance by his second wife. In great pain, he burned himself alive on a funeral pyre. Yet Zeus and the other gods accepted him after death on Mt. Olympus, the only human to achieve immortality. His splendid, but painful, life exemplifies the Greek belief that “those whom the gods love die young.” Better to go at the height of youthful strength and beauty.

Dr. Anne R. Bromberg, the DMA’s Cecil and Ida Green Curator of Ancient and Asian Art.