A new installation in the European Works on Paper Gallery contemplates the life and work of the German artist Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945). For Germans born in the latter half of the 19th century, life was in a constant state of chaos. Immigration to America was at an all-time high, and World War I would soon be on their doorstep only to be followed by the destruction of World War II. For Kollwitz, the impact of these grave events became the inspiration for her artwork.

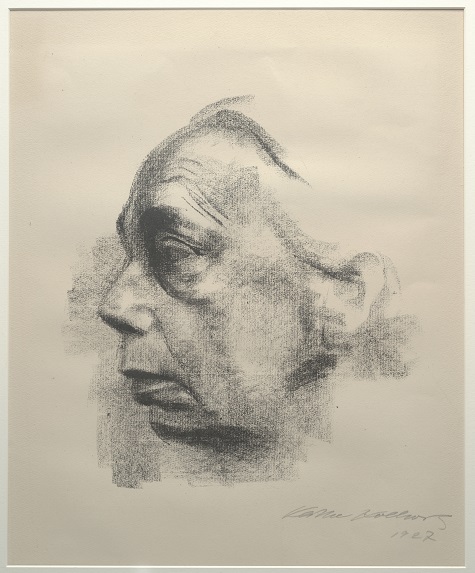

Käthe Kollwitz, Self-Portrait, 1927. lithograph, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alfred L. Bromberg

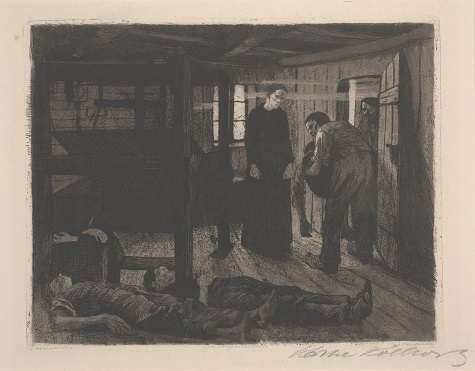

As a graphic artist and sculptor, Kollwitz was widely popular in Europe and America throughout her long life. Kollwitz had always been drawn to representing the working classes. But it was with a cycle of six prints documenting the Weaver’s Revolt of 1844 that she achieved instant fame. The DMA owns the last two prints in the series, Revolt and End.

Käthe Kollwitz, Revolt, 1897. ink and etching on paper, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts, The Alfred and Juanita Bromberg Collection, bequest of Juanita K. Bromberg

Käthe Kollwitz, End, 1897, aquatint and etching on paper, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alfred L. Bromberg

Together these works document the uprising of peasant workers and the resulting death and destruction. This series was so popular that Kollwitz was awarded a gold medal at the Great Berlin Exhibition of 1898, but the Prussian emperor Wilhelm II refused to award it to her, fearing her striking images would spark rebellions among the working classes. Nevertheless, it was this subject matter that would carry throughout her life’s work. She became dedicated to advocating for the lower classes and the downtrodden in society.

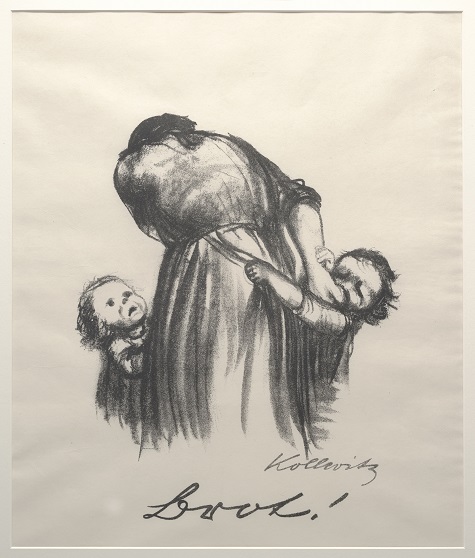

After the war, Kollwitz created many lithographs of women and children, such as Bread! and Hungry Children. These images were widely popular and circulated throughout the country. Kollwitz intended to draw attention to the starving working class and the impact of World War I on the nation.

Käthe Kollwitz, Bread!, 1924. lithograph, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alfred L. Bromberg

Käthe Kollwitz, Hungry Children, 1924. lithograph and ink, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts, The Alfred and Juanita Bromberg Collection, bequest of Juanita K. Bromberg

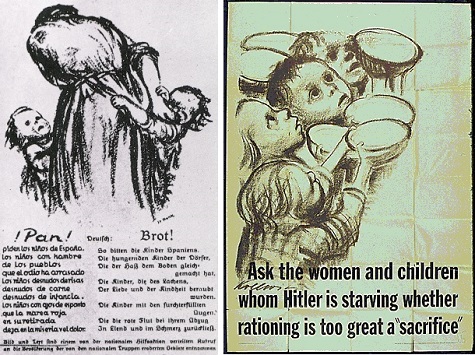

These two works were reprinted nearly a decade later. During World War II, Bread! was published in the National Socialist women’s magazine, Warte, as pro-Nazi propaganda, with the forged signature of St. Frank. Kollwitz was outraged, as she was a staunch opponent of Nazism and another world war. The United States appropriated Hungry Children as a propaganda poster to encourage rationing for the war effort.

After Käthe Kollwitz, Bread!, reprinted by the Nazi Party in NS Frauen Warte, the National Socialist Women’s Paper, photo credit Elizabeth Prelinger, Käthe Kollwitz (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1992), pg. 122. After Käthe Kollwitz , Ask the Women and Children Whom Hitler Is Starving Whether Rationing Is Too Great a “Sacrifice,” 1942-45, Photomechanical print, National Archives at College Park, MD, ARC Identifier, 513836

The works are currently on view in the Museum’s European Works on Paper Gallery on Level 2 and are included in the DMA’s free general admission.

Update September 5, 2014:

Listen to an interview with Michael Hartman discussing the exhibition on Tyler Green’s The Modern Art Notes Podcast here.

Michael Hartman is the McDermott Intern for European Art at the DMA.

How long will this be on exhibit?

It’s on view through November 16th!