The early 20th century was a time of accelerated transformation across fields, not unlike the present, and many viewed it as a time of new beginnings, not just politically but in technology, science, and the arts. Tumultuous change occurred with the rapid industrialization and mechanization of labor affecting, in turn, economics, science, and culture. This change also caused a growing philosophical division between nature and the machine to materialize; however, many artists, including Russian avant-garde artist El Lissitzky, saw an intrinsic connection between the two.

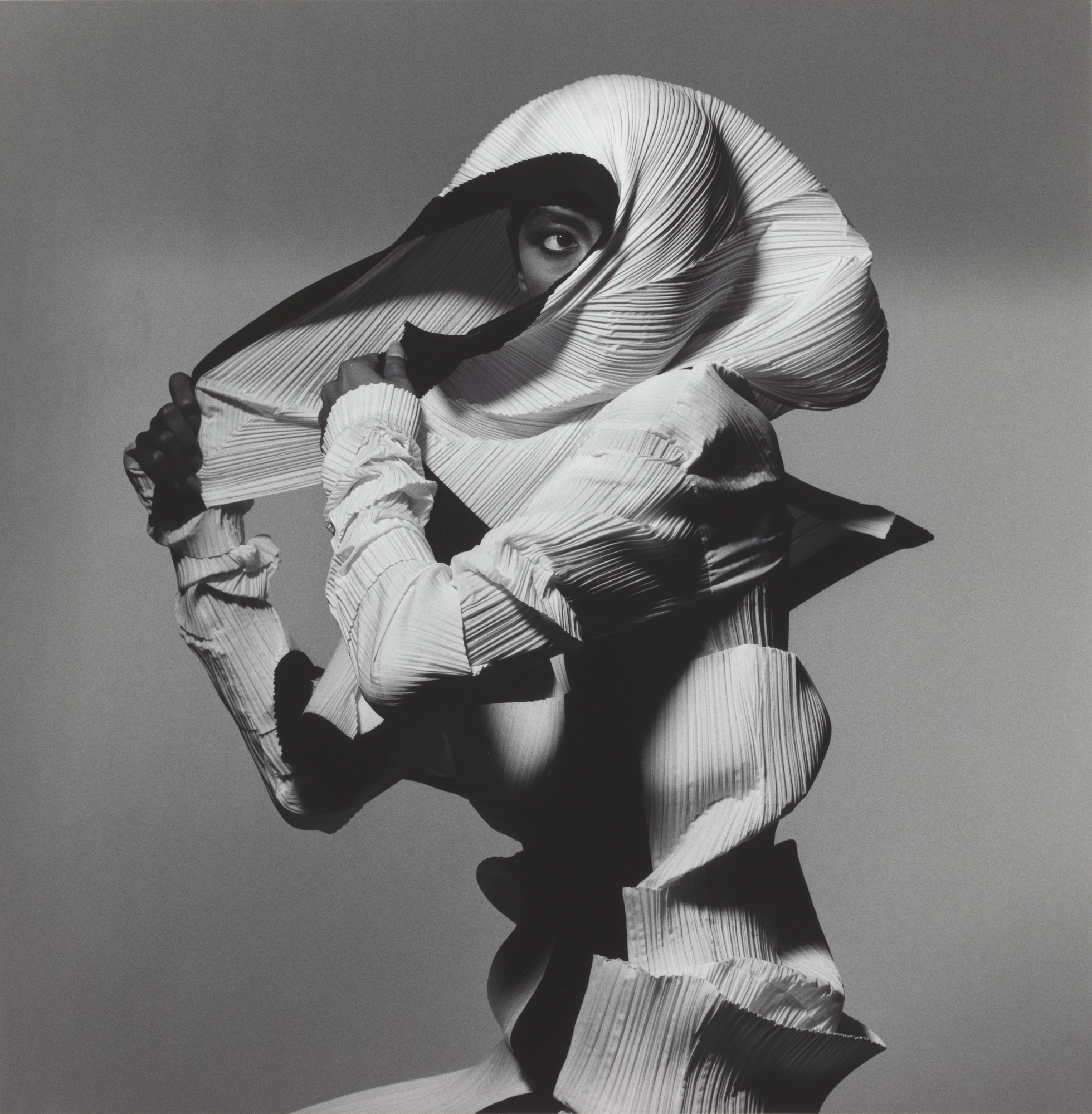

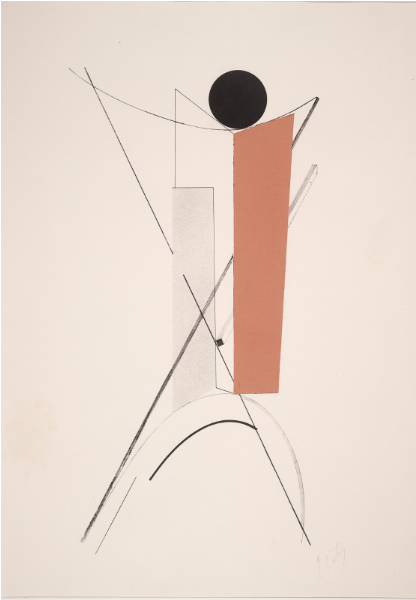

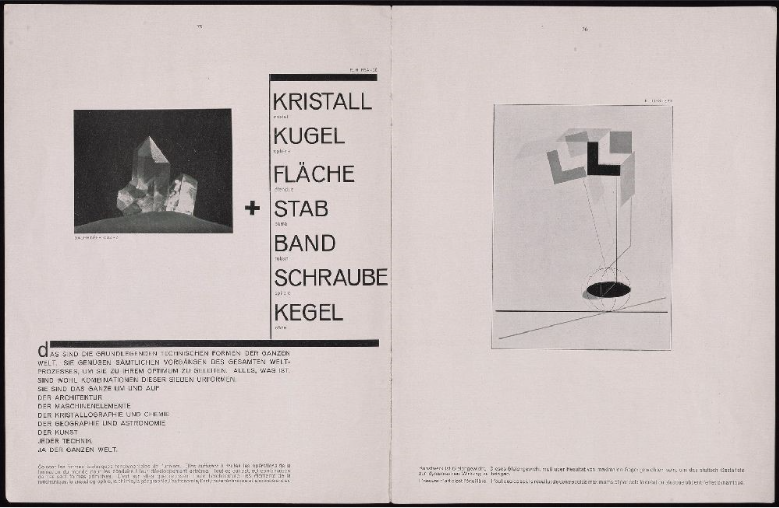

El Lissitzky (1890–1941) is one of the most influential and experimental Russian avant-garde artists of the early 20th century. His work as a designer, architect, photographer, and typographer explored the wider implications of the utility of art in everyday life. Within his extensive canon, Lissitzky’s most well known work is his Proun series, produced between 1919 and 1926. “Proun,” a term he invented that stands for the “project for the affirmation of the new,” is an amalgamation of visual elements from Suprematism, Constructivism, Futurism, and Cubism. An untiled plate from a collection of lithographs titled The First Kestner Portfolio (1923) [Image 2] is an example of this series and is currently on view in the DMA’s exhibition Movement: The Legacy of Kineticism. Abstract geometric forms weightlessly float within an altered perception of reality. Within the white space of infinity, a skeletal-like figure made up of crossed diagonals is strikingly architectural. Lissitzky’s work is often composed of a few neutral colors, reflecting a dynamic tension between two- and three-dimensional forms within the same space. Lissitzky viewed the Prouns as “the interchange station between painting and architecture,” which “goes beyond painting and the artists on the one hand and machine and the engineer on the other, and advances to the construction of space . . . [creating] a new, many faceted unity.”1 These works force the viewer to question their perception of reality, space, and time by processing multiple perspectives simultaneously.

In 1923 there was a distinct change in the non-objective painting practices of Lissitzky, the result of which can be seen in another untitled lithograph within the Kestner Portfolio (1923) [Image 3]. Embracing the technological advancements of industrial mechanization, artists explored the connection between nature and the machine, and the possibilities of art within this relation. Lissitzky explored newfound ideas wherein nature and technology were interconnected, and the dialogue between the mechanical and organic is present in the Kestner Proun’s elemental form.

Lissitzky described the Kestner Proun as a “Schwingungskorper,” or oscillating body emphasizing its dynamic functionality. To create the illusion of movement within the Kestner Proun, Lissitzky distilled implied movement via a subtle use of diagonal lines, the layering of transparent elements, repetition of form, and organic spheres. Though simple in its building blocks, the components are interacting on a holistic level. This complex system reverberates a kinetic energy as Lissitzky captures a frozen temporal moment.

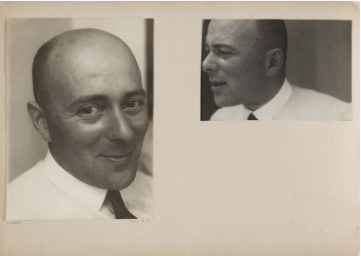

Lissitzky’s desire to construct forms through systems that are both mechanical and organic was inspired by the groundbreaking work of Austro-Hungarian microbiologist and popular science writer Raoul Heinrich Francé. Francé coined the word biotechnic, defining it as “the study of living and life-like systems, with the goal of discovering new principles, techniques and processes to be applied to man-made technology.”2 This methodology would later be called bionics. By the mid-1920s, scientists and laypeople alike read Francé’s writings on plants and soil microbiology, incorporating biocentrism into their own work. In addition to Lissitzky, Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, Laszlo Maholy-Nagy, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe also read Francé. Lissitzky’s letters reveal he contacted Francé in spring 1924, writing, “Thank you for Francé’s address. I will write to him when Nasci is ready and when I have read Bios [Francé’s book].”3[Image 4]

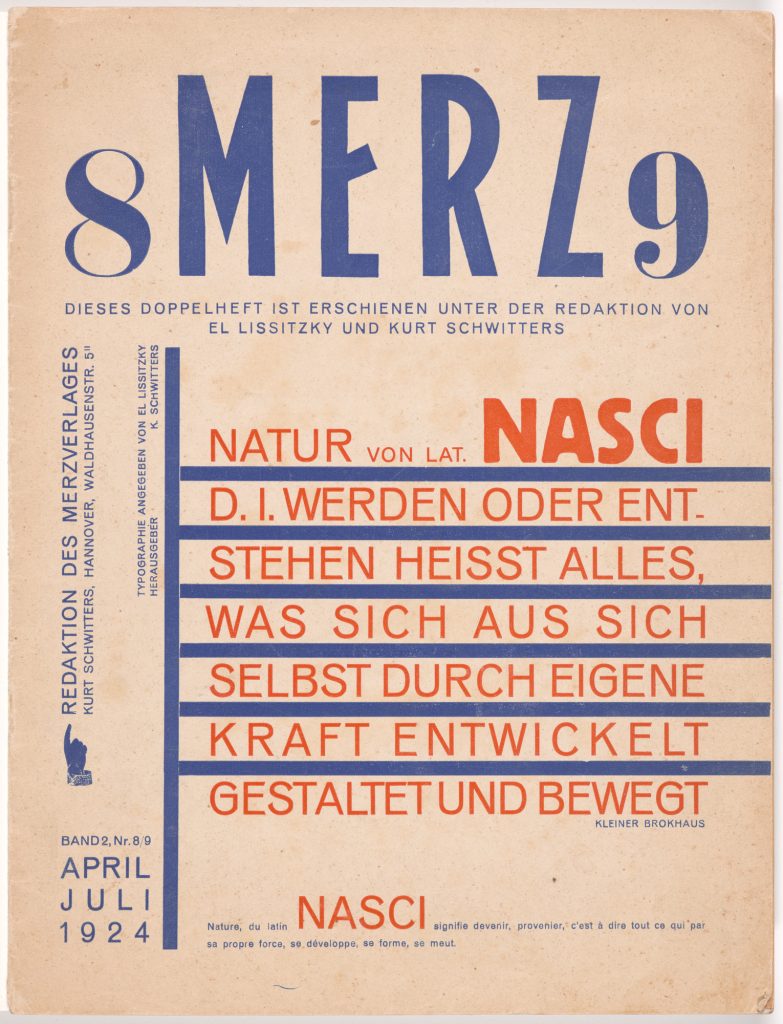

Directly influenced by Francé, Lissitzky denounced the machine in the summer 1924 publication of Nasci in the journal Mertz, which he co-edited with Dada artist Kurt Schwitters. The word nasci translates to “nature.” Lissitzky energetically argued in Nasci against claims that the machine had surpassed nature, suggesting by contrast that the machine was, in essence, nature itself because natural organisms, namely humans, made them. [Image 5] To prove this, Lissitzky curated a portfolio of new artworks that reflect Francé’s form-making philosophy, including his own Kestnermappe Proun (1923).

This clear declaration of the Kestner Proun as an example of biotechnical art strengthens the connection between Lissitzky’s bio-constructivist art with Francé’s concept of biotechnik. The elements within Kestner Proun, though simple in its building blocks, are interacting on a complex yet holistic level as they dynamically cross the white space of infinity. Creating a fully connected bio-mechanical system. The Proun now reflected a “frozen instantaneous picture of process, thus a work is a stopping-place on the road of becoming and not the fixed goal.”4 Lissitzky reconceptualized the creative process as an artistic machine reflecting nature as self-generating, embodying the evolutionary forces that proliferate organic forms. Here Lissitzky merges art, science, and design to create the unique collectivity that is biocentrism.

[1] Lissitzky-Küppers, Sophie. El Lissitzky: Life, Letters, Texts. Thames and Hudson Ltd, London. 1968, 347.

[2] Roth, Rene Romain. Raoul H. Francé and the Doctrine of Life. AuthorHouse, 2000.

[3]Lissitzky-Küppers, El Lissitzky: Life, Letters, Texts, 47.

[4] Lissitzky-Küppers, El Lissitzky: Life, Letters, Texts, 351.

Ashley McKinney is the Edith O’Donnell Institute of Art History Research Assistant for Indigenous American Art at the DMA