Artifacts, the DMA Member magazine, invited Jackson Pollock’s nephew Jason McCoy to share his thoughts on his uncle’s work on the eve of the DMA’s exclusive presentation of Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots, which opens on Friday, November 20. We hope you are as delighted by his article as we were to publish it.

Breakthrough: Pollock’s Black Paintings

By Jason McCoy

Original publish date: Artifacts Fall 2015

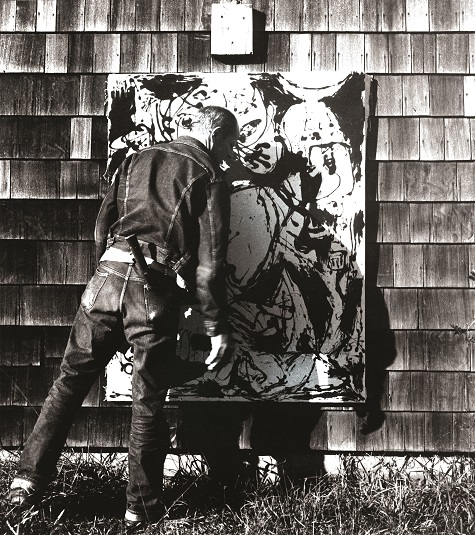

Jackson Pollock, n.d.

Photograph by Hans Namuth, Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona © 1991 Hans Namuth Estate

When DMA curator Gavin Delahunty first talked to me about his dream of organizing an exhibition of Jackson Pollock’s so-called Black and White paintings, I was of course intrigued but thought to myself “good luck.” It is notoriously difficult to organize any Pollock show, and I knew the paintings were scattered all over the world. But the good luck seems now to be ours—Gavin has pulled it all off and we have been given the great good fortune to be able to view the largest assemblage of these works together, ever. Jackson Pollock is one of the most recognizable names in modern art, but we generally associate the name not with a single image of a specific painting but rather with the idea of paintings that consist of masses of fine lines, skeined across the picture’s surface in seeming confusion.

I appreciate that the Blind Spots exhibition will present an additional view of Pollock’s oeuvre, the paintings that followed the so-called pourings. These paintings were yet another breakthrough for Jackson Pollock, because here he was able to convey the certainty and discipline of works that, for the most part, were made in one session. There is a clarity to the paintings, a minimalism and a simplicity that make it all look so easy and pre-ordained. Not so, of course, but what is revealed is a master’s ability to get it right the first time, and so let the paintings stand for themselves. They are a powerful, fascinating lot, crowned with one of my personal favorite paintings of all, Portrait and a Dream, a longtime resident of Dallas.

Blind Spots will enable all of us to reevaluate the breadth and depth of Pollock’s accomplishments. It will illuminate that there was most often a figurative element in all of Pollock’s paintings, as images of man or beast are easy to recognize in Pollock’s first gestures on the plane. We can recall a comment he made to this effect, that in these paintings the “figure is coming through.” Such recognizable forms in fact caused consternation with certain modernist critics at the time, who did not care to acknowledge less than fully abstract painting as being modern.

Blind Spots will also include examples of Pollock’s interest in scale. In 1951, with the help of his brother, Sanford McCoy, he chose six paintings not at all similar in size to be used in a suite of serigraphs, a selection of which are exhibited in this exhibition. With a computer today, this type of curiosity might seem obvious, but this was not the case sixty-five years ago.

Had Pollock stopped after his “drip paintings” of the late 1940s he would certainly still have his place in history. Rather, his creative drive was such that it continued to evolve in unexpected ways and cover new ground, as Blind Spots reveals, accentuating that Pollock’s gift was much more than one-dimensional.

Untitled, n.d., Photograph by Hans Namuth, Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona

© 1991 Hans Namuth Estate

–Jason McCoy is President of Jason McCoy Gallery in New York.

For more stories like the one above, all of which were created exclusively for Artifacts, visit DMA.org/members.

(image: Jackson Pollock, Portrait and a Dream, 1953, oil and enamel on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Algur H. Meadows and the Meadows Foundation, Incorporated © 2015 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)