Months. It took literally months during the summer of 2014 to decide on the orthography (the correct spelling/writing) for the exhibition Inca: Conquests of the Andes/Los Incas y las conquistas de los Andes, which opened Friday. For example, should the Museum use “Inca” or “Inka,” among other spelling differences that would emerge in the exhibition texts. Many factors weighed into my decision, from popular recognition to modern linguistics, from consistency in labels to proper pronunciation. For the first few months of the exhibition project, I solicited the opinions of many individuals about the issue—from leading pre-Columbian linguists to Inca archaeologists to fellow curators, and even friends and family. I read the most recent publications, edited volumes, scholarly monographs, and online blogs to ascertain the most current opinions. Indeed, I researched, inquired, and deliberated so long that there was general confusion around the DMA itself about the final decision for months after I had finally settled on a position. Mea culpa; thank you to everyone for their kind patience. And I appreciate the generous input from many colleagues on an issue that elicits deep passion and strong opinions from scholars across disciplines.

Quipu (Khipu) fragment with subsidiary cords/Quipu (khipu) parcial con cuerdas afiliadas, Peru, Andean highlands or coast, Inca (Inka) culture, A.D. 1400–1570, cotton and indigo dye, Dallas Museum of Art, the Nora and John Wise Collection, bequest of John Wise, 1983.W.2174

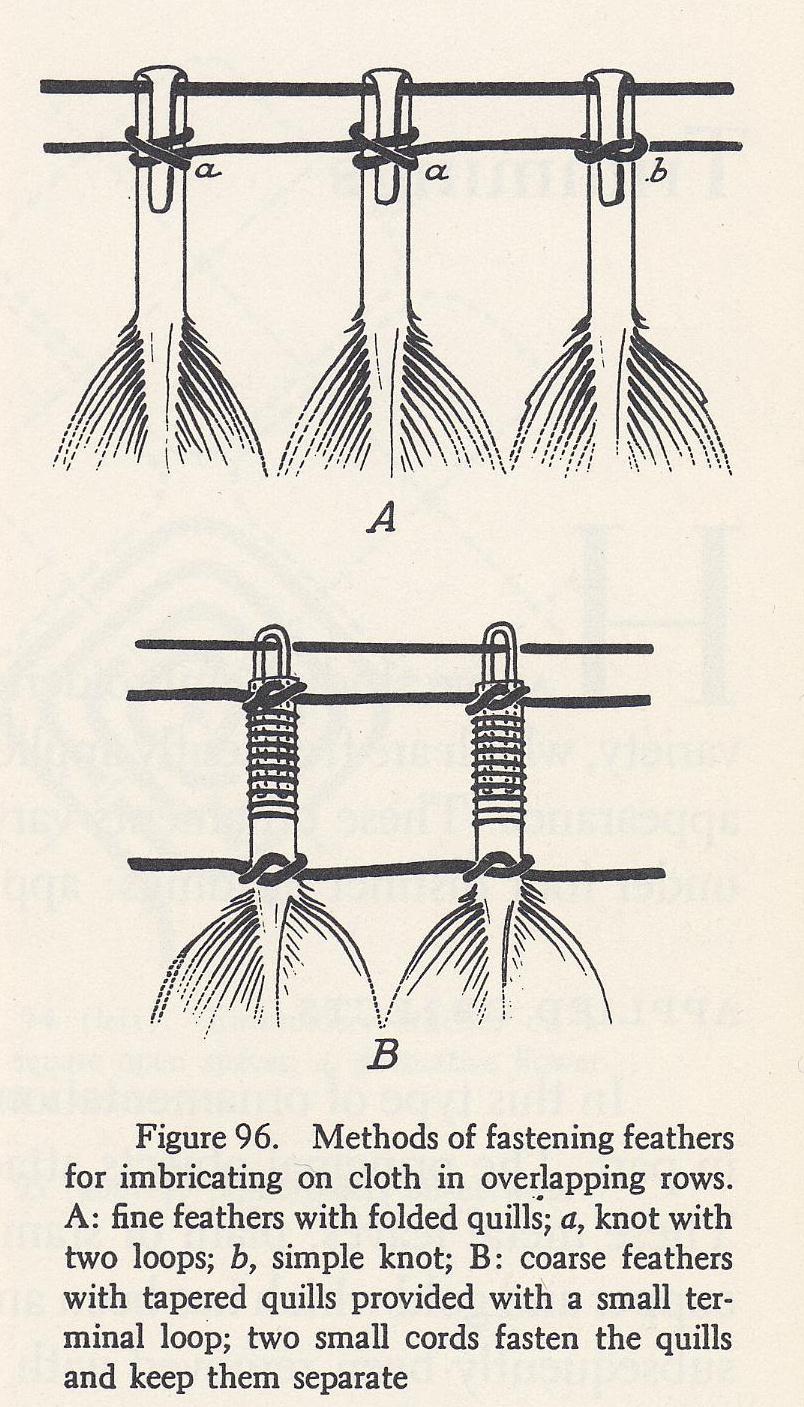

The central issue is this: What is the ideal manner—in a US public exhibition context—for writing words from Runasimi, or Quechua, the language used as a lingua franca by the Inca state system and spoken today by many Andean peoples. Prior to the Spanish arrival in the 1530s, the Andean populations did not utilize a recognizable written script, one that the Spanish acknowledged and transcribed into a phonetic alphabet, as certain Spanish chroniclers attempted in New Spain. The Andean knotted cords, or quipu (khipu), that recorded information were documented by certain chroniclers in South America, who noted that the quipu were used to register taxes and census data, among other information. The individual Spanish chroniclers further documented Quechua words in the phonetic alphabet and according to Spanish pronunciation, with variant spellings. Certain spellings gained in pronunciation, popular recognition, and adoption into English.

Since the mid-20th century, there have been great efforts to revise the orthography of Andean languages, in particular Runasimi (Quechua), with laws passed in Peru during the late 1970s and early 1980s. The revised orthographies introduced changes such as the reduction from a five-vowel alphabet to a three-vowel system for Quechua. Modern linguists, such as the Peruvian scholar Ramon Cerrón-Palomino, have provided welcome standards for ongoing publication in Inca and Andean studies.

Four-cornered hat/Gorro de cuatro puntas, Peru, south-central highlands or coast, Huari (Wari) culture, A.D. 700–900, camelid fiber, Dallas Museum of Art, The Nora and John Wise Collection, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Jake L. Hamon, the Eugene McDermott Family, Mr. and Mrs. Algur H. Meadows and the Meadows Foundation, Incorporated, and Mr. and Mrs. John D. Murchison, 1976.W.2013

As an Andean scholar, I had actively used many revised spellings in teaching and coursework, as well as in a recent 2013 exhibition, Between Mountains and Sea: Arts of the Ancient Andes, at the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas. Upon joining the DMA, I had further standardized the terms within the Museum’s database, emphasizing the revised spellings of Wari (for Huari), Tiwanaku (for Tiahuanaco) and Inka (for Inca). With specialization in the cultures of the Formative Period and the north coast of Peru, I confess to addressing only superficially the issue of orthography prior to the DMA exhibition. The spellings of the Cupisnique, Moche, and Chimú—the successive north coast cultures—have remained relatively constant. So I had adopted the basic premise that to utilize the new Quechua spellings was to honor indigenous rights, which aligns well with my role as a researcher of Andean cultural heritage.

Through the months I spent researching, however, the issue became less black and white for this context; it came to include various factors regarding public recognition and spelling consistency through the exhibition design. In the end, the decision to maintain historical spellings as the primary terms in the Inca exhibition likewise presented the wonderful opportunity to introduce an audience to corresponding Quechua spellings. The exhibition Inca: Conquests of the Andes/Los Incas y las conquistas de los Andes thus features not only English and Spanish text but also dual spellings for most Quechua terms. A wall panel explaining the chosen orthography opens the exhibition, providing viewers with an opportunity to consider the complex ways language records, reflects, and defines a historical culture.

Kimberly L. Jones, PhD, is The Ellen and Harry S. Parker III Assistant Curator of the Arts of the Americas at the DMA.