The centerpiece of Ida O’Keeffe: Escaping Georgia’s Shadow is her Highland Lighthouse series. Ida Ten Eyck O’Keeffe painted seven variations of the lighthouse in the early 1930s, using mostly related color palettes and experimenting with dynamic symmetry. The first, a realistic representation, is now lost, but the following six lighthouses she painted are all reunited here at the DMA in one room.

- Ida Ten Eyck O’Keeffe, “Variation on a Lighthouse Theme II,” c. 1931-32, oil on canvas, anonymous lender, 117.2017.01

- Frame detail, photograph by author

Five of the paintings have a “clam shell” frame. The sides of a clam shell frame slope inward toward the painting. Each side is half of an arch that peaks at the inner edge where the frame meets the canvas. These frames were all made by painter and frame maker George F. Of, who worked closely with Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 gallery. Thus, it is through her relationship with her sister Georgia and her brother-in-law Alfred Stieglitz that Ida came to know Of during the early years of her career.

Ida’s paintings are not the only example of close working relationships between artists and frame makers on view at the DMA. Artists often worked closely with particular frame makers and some were known to prefer certain styles of frames.

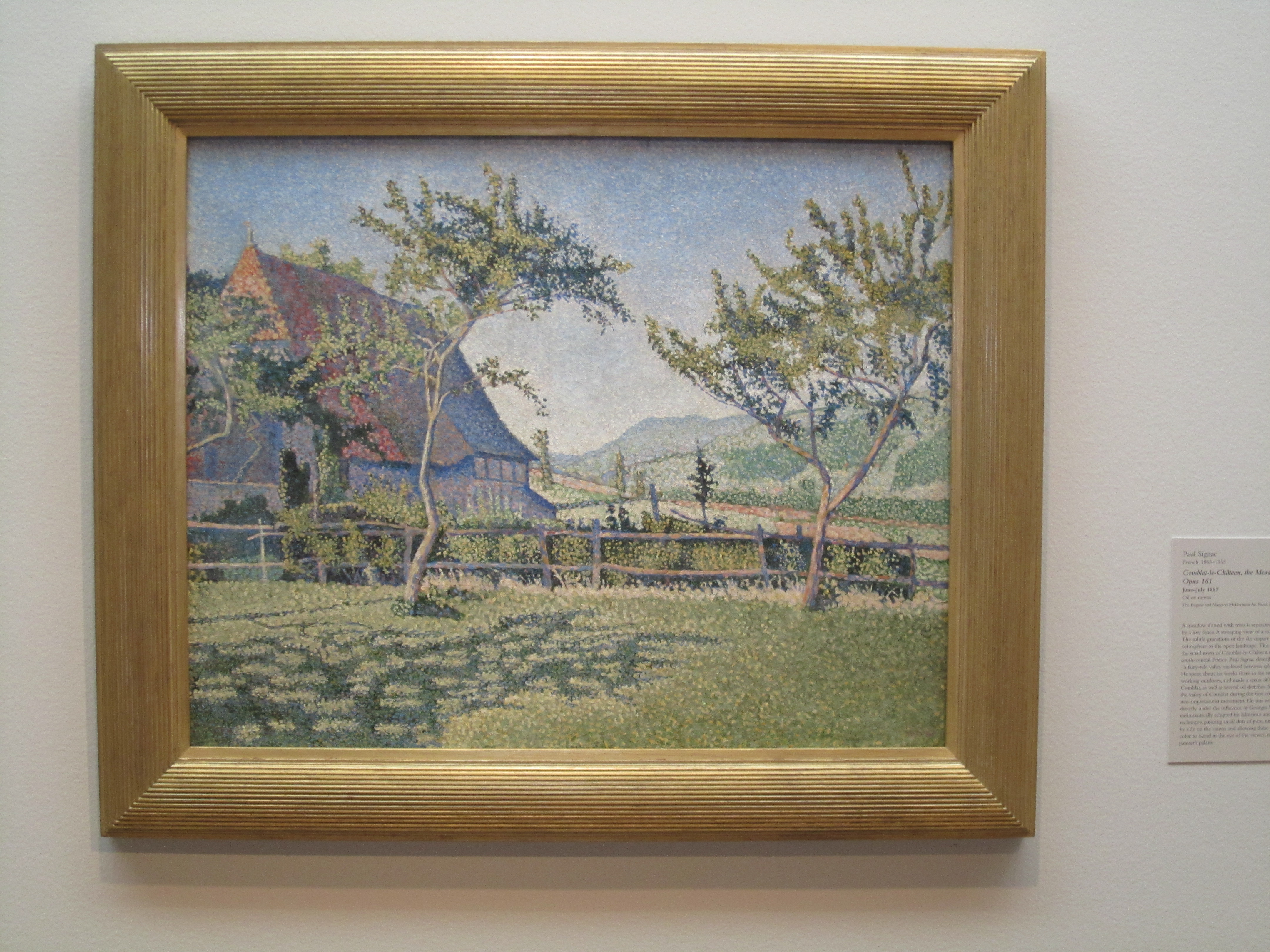

Maurice Prendergast, Merry-Go-Round, c. 1902-06, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, The Eugene and Margaret McDermott Art Fund, Inc.

On view in An Enduring Legacy, Maurice Prendergast’s painting Merry-Go-Round is in a frame that was probably not made by his brother Charles. Many other artists of his time mechanically reproduced patterns for their frames, but Charles designed and hand carved his frames. He considered himself an artist too. If he made a frame for Merry-Go-Round, it was long gone when it entered the McDermott’s collection. Margaret McDermott chose this frame to accentuate the style of the painting.

The frame has both an inner and outer edge of roughly carved wood in ropelike patterns. Between these layers is an expanse of unvarnished wood with groups of scratches perpendicular to the painting’s edges. The unfinished quality of the wood frame complements the blank canvas that is visible throughout the painting where colors meet.

- George Wesley Bellows, “Emma in a Purple Dress,” 1920-23, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas Art Association Purchase, 1956.58

George Bellows’s portrait of his wife, Emma in a Purple Dress, is in a “Bellows frame.” Bellows favored frames by the New York frame maker M. Grieve Company. This particular water-gilded gold frame has three thin, curved ridges descending toward the painting within a squared outer frame. Its back is stamped with “Grieves Co.” The gilded, textured surface of the frame emphasizes the shining fabric of the sitter’s dress.

Reviews of Ida O’Keeffe’s New York shows sometimes mention her tendency to decorate her own frames, though few of them survive today. Ida most likely didn’t make the frame for Star Gazing in Texas, but she did decorate its upper molding with star-shaped foil stickers and five-point stars cut from tin.

- Ida Ten Eyck O’Keeffe, “Star Gazing in Texas,” 1938, oil on canvas. Dallas Museum of Art, General Acquisitions Fund and Janet Kendall Forsythe Fund in honor of Janet Kendall Forsythe on behalf of the Earl A. Forsythe family, 2017.36

- Frame detail, photograph by author

These stars on the frame make it part of the composition. The title, Star Gazing in Texas, reinforces the relationship between painting and frame. During Ida’s lifetime, the painting was exhibited under several other titles—Dreaming in Moonlight; Spring Lethargy, Texas; and, possibly, Texas Hillbillies. The DMA’s Pauline Gill Sullivan Curator of American Art, Sue Canterbury, chose the title Star Gazing in Texas, which Ida used in an inventory of her paintings, because it captured the interconnectivity of the painting to its frame. The star-gazing woman looks outside her painted environment, making the frame part of her world as well as part of ours.

Rebecca Singerman is the McDermott Graduate Intern for American Art at the DMA.