When you enter the Southeastern Asian galleries located on the third floor of the Museum, an instant calm envelops you. The gallery is full of stone and bronze figures choreographed in slow and quiet poses. It’s almost like stumbling upon a yoga class, where each figure is in a tranquil pose and reaching for spiritual awareness.

I am most drawn to the bronze sculptures of the collection, and I’d like to share how they were made. As with most metal sculptures throughout history, the sacred bronzes of India were made with the ancient technique of the lost-wax process. The lost-wax process served as an integral part of the Hindu religion during the Chola dynasty, which reigned between the ninth and thirteenth centuries, due to the desire for portable images of deities.

These bronze figures were created for worship and were housed in stone temples. Oftentimes, they were removed from the temples for use in ceremonies, acting as processional gods to the people of India. Our very own Shiva Nataraja is a perfect example of a processional bronze. For more information on how these bronze objects were used in ceremonies, read Hannah’s blog post on Thursday.

Shiva Nataraja, India, c. 1100, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. Eugene McDermott, the Hamon Charitable Foundation, and an anonymous donor in honor of David T. Owsley, with additional funding from The Cecil and Ida Green Foundation and the Cecil and Ida Green Acquisition Fund

Lost-wax Process

The lost-wax process is a technique that seems to be as old as time. It’s estimated that the earliest work created in this technique dates back to around 3500 B.C. in modern day Pakistan, and it is a common application for sculptors today. One of the oldest works we have in the Museum dates back to 2000 B.C. and can be found in Silk Road installation on the third floor.

The process begins with “prepared wax,” a mixture of hard beeswax and resin. The sculptor gently heats the wax to create a malleable material for molding. After an area of the object is finished, it is dipped into a cold basin of water to harden the wax. This alternation of heating and cooling continues until the entire figure is assembled. The sculptor will then go back and add details with wooden tools to finalize the figure.

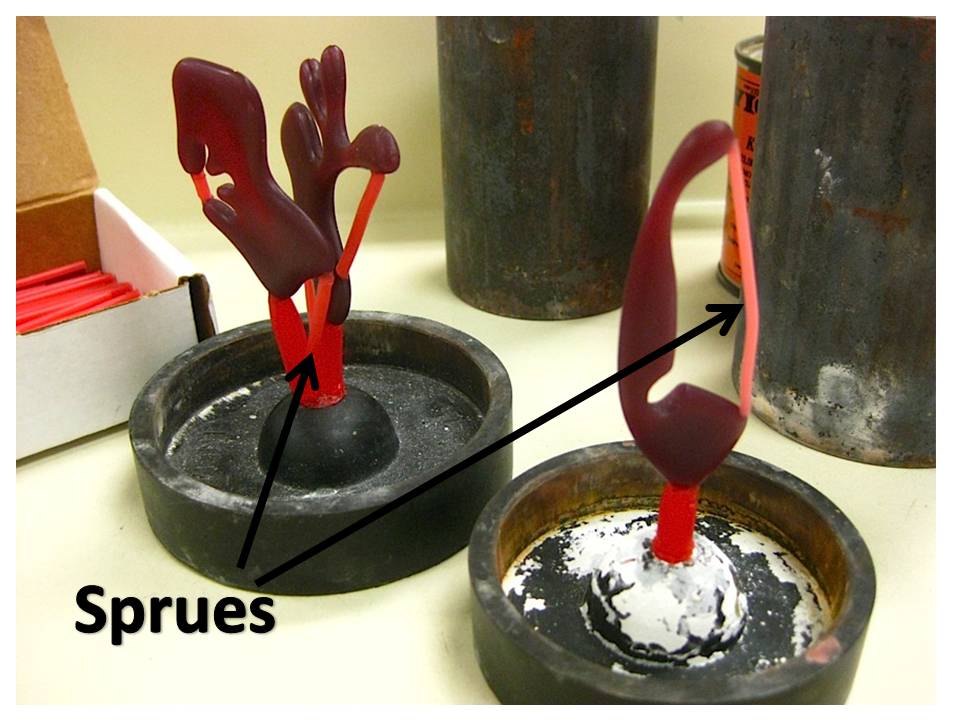

Once the object is ready for the mold, sprues (which are tubular forms of wax that allows liquid metal to flow from one end to another) are applied to the figure to ensure that the molten metal will reach all parts of the figure. The sculptor then meticulously applies several layers of clay to build up a mold, leaving a small hole to allow for the burn-out process. When the clay is bone-dry, the mold is fired to harden the clay and to burn-out the wax. This method allows the wax to flow out, leaving a hollowed clay mold.

Next, metalworkers melt a mixture of copper, lead, and tin (and in some cases, gold and silver too) in a crucible and then carefully pour the molten metal into the same hole the wax was released from. Metal cools relatively fast, so if you have a large object, you have to make sure you have enough melted metal! Once the metal is cooled, the clay shell is broken and the sculpture is revealed. Every bronze sculpture is unique, as the clay molds cannot be reused. To complete the work, the sculptor must cut off the sprues and sand the surface smooth, readying the object for the final application of polishing and wax.

I encourage you to stop by the Museum and observe these sacred bronzes of India. You might find yourself appreciating the tranquil rhythm and balance of these forms, as well as how they were made!

Best regards,

Loryn Leonard

Coordinator of Museum Visits