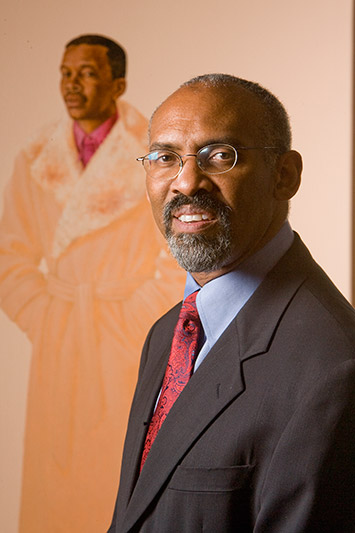

Regarded as one of the premier art historians on the Harlem Renaissance, Dr. Richard Powell will be joining us on Friday, May 18, for our Late Night celebration centered on the Harlem Renaissance and the Youth and Beauty: Art of the American Twenties exhibition.

Dr. Powell, the John Spencer Bassett Professor of Art & Art History at Duke University, has been writing on art and curating since 1988, when he received his Ph.D. from Yale University. He has worked with the Studio Museum in Harlem, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. We asked him a few questions about his work before he joins us on Friday.

You’ve worked extensively on African diaspora, American art, and African American art. What drew you to the Harlem Renaissance specifically?

So much of the work during this period was trail-blazing. It was pushing against conventions to make a bold, new statement in art.

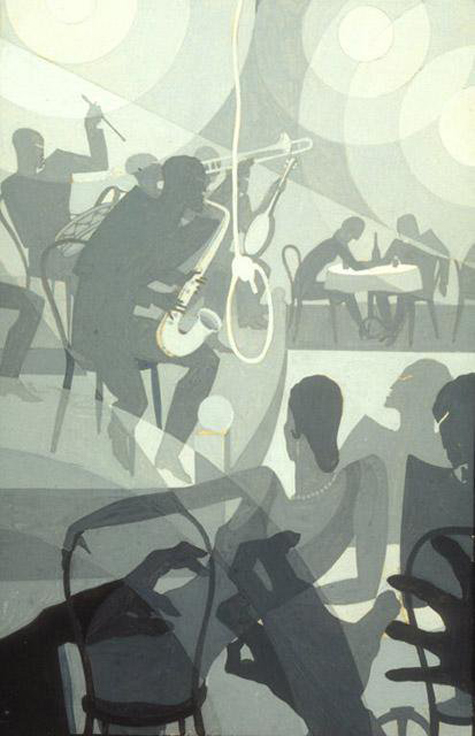

Would you comment on the work Congo (1928) by Aaron Douglas, which is featured in Youth and Beauty, and how it is evocative of the Harlem Renaissance?

It is evocative of the Harlem Renaissance because Douglas is encouraging viewers to see African dance, bodies, and art as sources of inspiration and information. My favorite part of the picture is the woman looking upward with what seems like “super sight” Eyes that radiate upward on a levitating figure. Eyes that do more than simply see; they project.

Aaron Douglas, Congo, c. 1928, gouache and pencil on paperboard, North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, Gift of Susie R. Powell and Franklin R. Anderson

Do you have a favorite, little known fact or story about the Harlem Renaissance?

My little known fact is that the term “Harlem Renaissance” actually comes into common currency starting in the 1940s. Artistically inclined black artists in the 1920s and 1930s referred to that moment as the “New Negro Arts Movement.”

What are you most looking forward to on your visit to Dallas?

Just seeing Dallas. It’s been a little while since I was last there. I’m really looking forward to my visit!

Dr. Powell’s lecture, Jungle Beauty: Harlem Renaissance Portraits and Their Marks, will start at 9:00 p.m. in Horchow Auditorium on Friday, May 18. We hope to see you there!

Liz Menz is the Manager of Adult Programming.