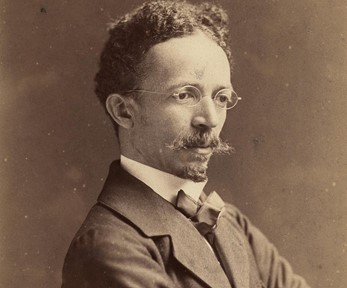

This month the DMA celebrates the acclaimed African American artist Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859–1937). Tanner’s intimate painting Christ and His Mother Studying the Scriptures is one of the cornerstones of our American collection. He rendered the lush, densely painted surface using a restricted palette predominated by shades of cool, luminous blue. The color became so synonymous with him that it earned the nickname “Tanner-blue.”

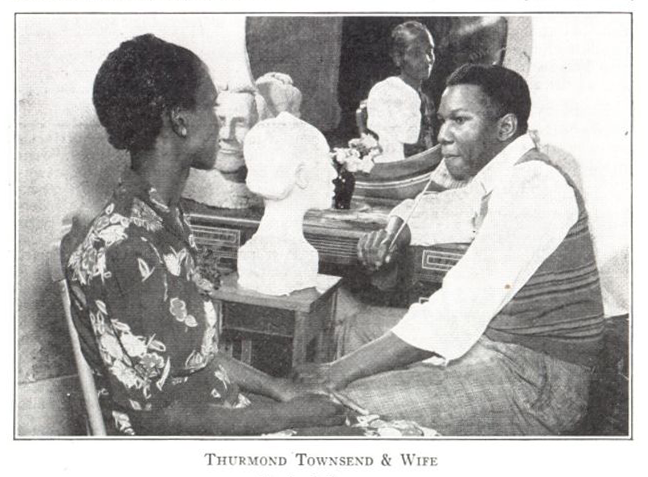

The artist’s wife, Jessie Olssen, an American opera singer living in Paris when they met, and their young son, Jesse, often served as his models. Two existing photographs (figs. 1 & 2) confirm they posed for him as he considered different arrangements for the DMA’s painting, and one (fig. 1) was the template. That they posed for this painting makes it simultaneously a meditative religious scene and a tender family portrait.

Tanner seems to have been so enamored with the composition that three years later he rendered a similar version, Christ Learning to Read. He made slight changes to the poses of Christ and Mary and experimented with an impressionistic application of a high-keyed pastel color palette to render light. Further, the painting’s structural frame and inner arcing spandrel reflect the influence of buildings he most likely saw during his many trips to Morocco.

Tanner’s decision to be a religious painter was deeply rooted in his family background. His father, Benjamin Tucker Tanner (1835–1923), was a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and the artist’s childhood home was a well-known salon of Black culture in Philadelphia. Nevertheless, it is not surprising that his path to a successful career was filled with many obstacles. While he found studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts with Thomas Eakins intellectually fulfilling, the extreme racism he experienced from classmates was intolerable. Acknowledging that he “could not fight prejudice and paint at the same time,” Tanner left Philadelphia, briefly set up a photography studio in Georgia, and eventually lived out his life in Paris as an American expatriate. The city was culturally, socially, and artistically welcoming, while also providing him with the freedom and camaraderie unavailable to him in his segregated homeland. In Paris, the shy, serious-minded artist flourished and prospered. After a trip to Palestine, Tanner turned his focus toward painting biblical scenes and rarely strayed from this theme for the rest of his life.

Both the Dallas and Des Moines paintings, along with the two photographs discussed here, are emblematic of Tanner’s devotion to his faith and career, and all of them serve as affectionate double portraits in tribute to his wife and son. The Dallas Museum of Art is proud to display Christ and His Mother Studying the Scriptures, which is a masterpiece by this admired and accomplished American artist, in our galleries. We are always honored to celebrate Tanner’s life, legacy, and contribution to the canon of American art, and we are most especially pleased to do so during Black History Month.

Martha MacLeod is the Senior Curatorial Administrator and Curatorial Assistant for Decorative Arts and Design, Latin American Art, and American Art at the DMA.