Artists Casey Koyczan and Eric Wagliardo each learned about rock art as many of us do—as a child or young adult in school, or out of an abundance of curiosity about the past, archaeology, or ancient art. But Koyczan, a Dene interdisciplinary artist from Yellowknife, Canada, says, “[I]t wasn’t until adulthood that I was able to experience them in person and fully realize their importance and spiritual meaning.” Also called petroglyphs (etched or pecked images) or pictographs (painted images), rock art has been created for thousands of years by people around the globe, from Australia to South Africa to Europe. Take, for example, the famous cave paintings at Lascaux and Chauvet, France, which include stunning depictions of horses, mammoths, bulls, and handprints. These are approximately 22,000 and 36,000 years old, respectively. Globally, the representations of humans, living and extinct animals, mythical beings, and abstract images portrayed in rock art can be an important part of the spiritual inheritance and identities of contemporary Indigenous peoples.

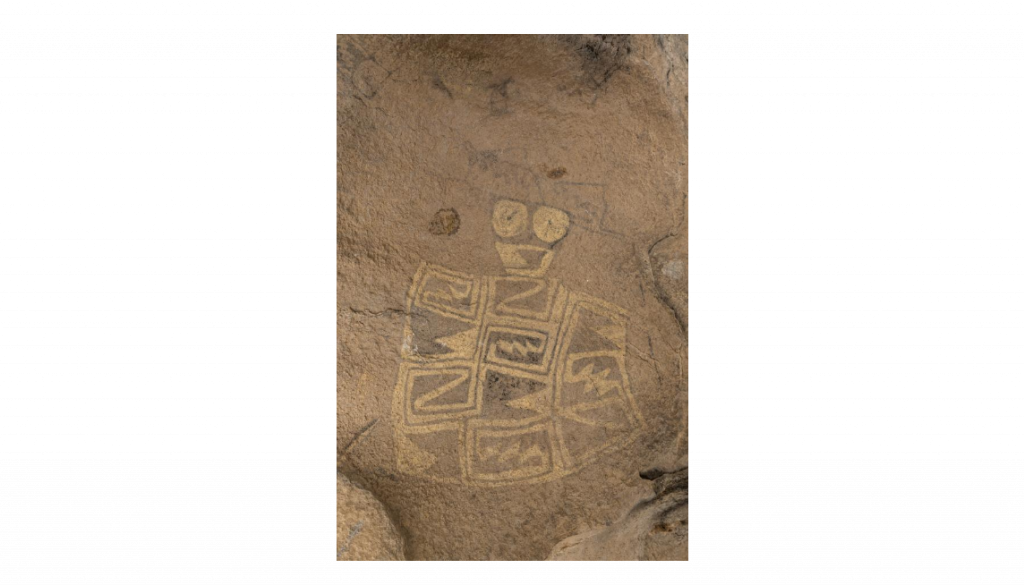

Across North America, notable rock art sites were produced by ancestral Indigenous inhabitants at locations like Jeffers Petroglyphs in Minnesota (8,000 images in one place!); Newspaper Rock, Canyonlands National Park, Utah; and Petroglyphs Provincial Park, Vancouver Island, Canada. However, while researching this project, Texas-based artist Wagliardo was surprised to learn that petroglyphs and pictographs exist right here in Texas—a fact that might astonish many Texans. Pictographs at Hueco Tanks State Park east of El Paso and Seminole Canyon State Park near Comstock are among the most well known sites in the Lone Star State.

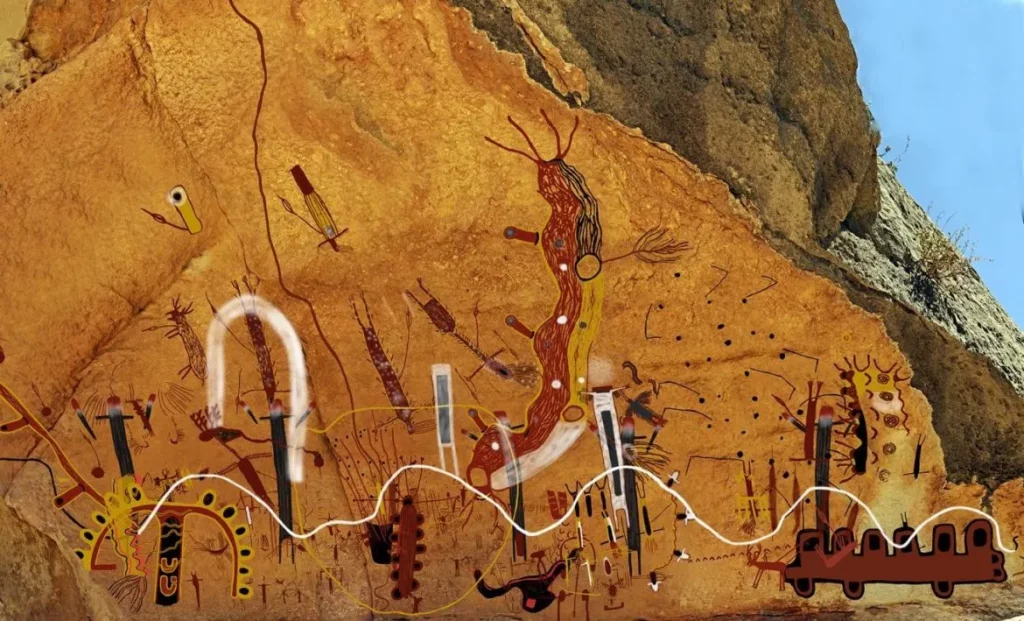

Ha Ilè (pronounced ha-ee-lay) is an augmented reality (AR) rock art installation created by Koyczan and Wagliardo. AR allows semi-realistic experiences of an object or environment that can be interacted with in a seemingly real or physical way. By scanning a QR code, DMA visitors can take part in a unique Ha Ilè experience at two building entrances—pictographs on rock at the Ross Avenue entrance, and a charismatic hummingbird at the entrance adjacent to Klyde Warren Park. Ha Ilè can also be experienced at other locations, including the AT&T Discovery District.

Representing one of the world’s oldest art forms using cutting-edge technology is an innovative approach—Koyczan and Wagliardo generated the rock forms through 3D scanning and produced the pictographs through artificial intelligence (AI) to portray rock art from North America and across the world; and, finally, the hummingbird is a computer-generated simulation of a three-dimensional image. Hummingbird motifs have been depicted throughout time across the Americas; Koyczan and Wagliardo discovered while working on Ha Ilè that they both cherish the beautiful and sometimes fierce migratory bird.

Ha Ilè means future and past tense in the Dene language. Koyczan proposes that this work has the potential to exist for as long as the petroglyphs and pictographs that inspired it, and he feels “it relates heavily to Indigenous Futurisms and how humanity will view and experience artwork in the future.” Indigenous Futurisms is defined as a movement consisting of art, literature, and other media that express Indigenous perspectives of the future, past, and present, typically in the context of science fiction. Expressing a similar sentiment, Wagliardo is hopeful that “these pieces help people reconnect with the past and imagine an optimistic future where we as a society connect in a deeper, more meaningful way.”

Ha Ilè is on view at the DMA through January 31, 2023. To learn more about Texas rock art, please visit the Shumla Archaeological Research & Education Center https://shumla.org/ or the Texas State Historical Association https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/indian-rock-art.

Ha Ile is courtesy of the Government of Canada; the Consulate General of Canada, Dallas; the City of Dallas, Office of Arts and Culture; and the Dallas Museum of Art. The Dallas Museum of Art is supported, in part, by the generosity of DMA Members and donors, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Texas Commission on the Arts, and the citizens of Dallas through the City of Dallas Office of Arts and Culture.

Dr. Michelle Rich is The Ellen and Harry S. Parker III Assistant Curator of Indigenous American Art at the DMA.