The Dallas Museum of Art was given the opportunity to exhibit a collection of exceptional Frida Kahlo works. In preparation for their display on February 28, 2021, three of the paintings were studied in the paintings conservation studio, including Still Life with Parrot and Flag from 1951, Sun and Life from 1947, and Diego and Frida 1929–1944 from 1944. Using infrared photography, X-radiography, and microscopic examination, novel information was brought to light regarding each work.

Infrared photography allows conservators to look through surface level paint to the underlying preparatory layers. X-radiography, on the other hand, allows us to visualize compositional changes made in paint. This type of imaging provided a fascinating perspective into Frida Kahlo’s working practice.

In Still Life with Parrot and Flag, an initial planning drawing done in both thin lines and wide ink strokes shows how Kahlo simplified compositional elements in the final painting, especially with regards to shifting the size and shape of the fruits. The most labored part of the underdrawing shows several adjustments made to the parrot’s wing and beak, and changes made to the adjacent mango. The blue lines overlayed onto the visible light photograph represent a tracing made from the IR photograph of the most prominent changes Kahlo made to this initial underdrawing. The underdrawing observed in each painting made clear that Kahlo had a strong vision for the overall composition of each work, regardless of the subtle changes made in the painting process.

IR photography also revealed a small inscription on one of the shells attached to the frame on Diego and Frida. This inscription reads “Recuerdo de Veracruz” and was subsequently covered up by red paint, probably by Frida herself. Frames like this one would have likely been found in the tourist market of Veracruz; here, it is a special hidden detail giving us an intimate glimpse into the past life of the object.

The X-ray taken of Sun and Life revealed an exciting evolution observed in the painting: although Kahlo’s basic composition was generally set from the underdrawing to the early painting phase, the details evolved significantly in later phases of painting. The plant pods surrounding the sun, for example, largely began closed but opened gradually during the painting process. Another interesting discovery was the fetus-like element directly behind the sun that emerged as Frida finalized the painting, in contrast to the X-ray that reveals a closed pod. The blue lines overlaid onto the visible light image of the painting represent a tracing made from the X-ray and indicate where compositional changes took place during the painting process.

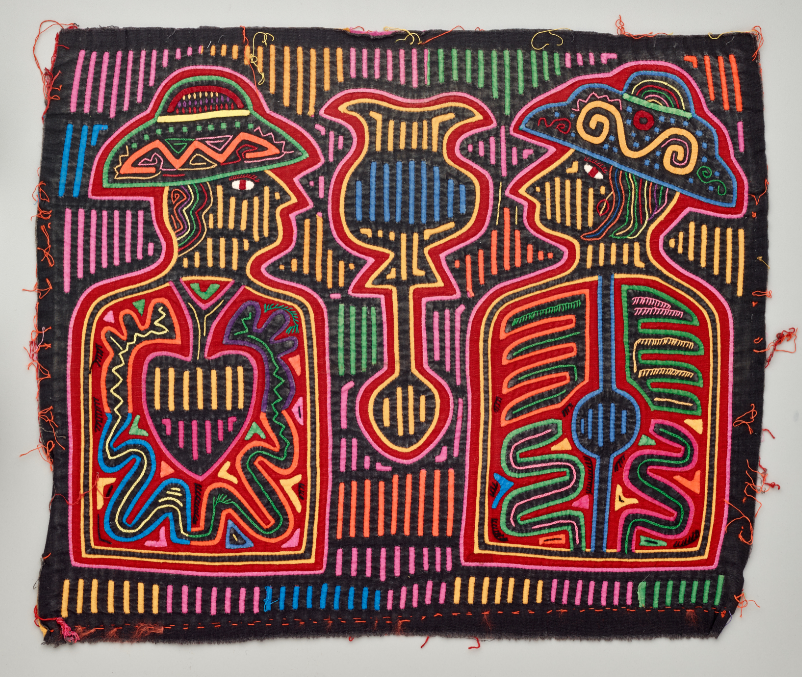

Kahlo’s brushwork is stunning, utilizing a vast array of application techniques and styles to create movement and texture in each work. In Still Life with Parrot and Flag, her use of small rapid, brushstrokes achieves a composition of intricately varied textures and color, while long, sinuous strokes are used predominantly in Sun and Life. Frida and Diego takes a more direct painting technique of highly textured paint applied in short, tiny strokes. It is interesting to note that in two of the paintings, impressions of Frida’s fingerprints are visible in the paint—a subtle hallmark that humanizes the work.

Varied painting techniques shown in close-ups of her works

It was a privilege to examine these great works together with Dr. Mark A. Castro and Dr. Agustín Arteaga. I hope you enjoy this special moment to see the works together.

Laura Eva Hartman is the Paintings Conservator at the DMA.