It has been a few years since the DMA has hosted a photography exhibition, and it has been a real treat to present Irving Penn: Beyond Beauty—the artist’s first retrospective in 20 years and the first since his death. While Penn is well known for his work in fashion and portraiture for magazines like Vogue, the exhibition also features some of his lesser-known, personal work, like his street photographs and a series of nudes.

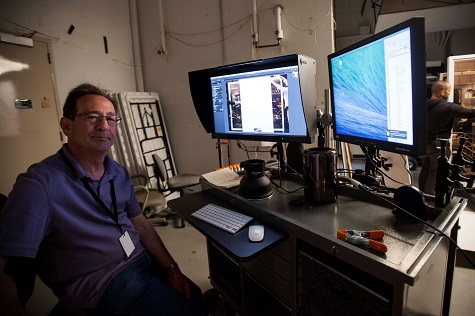

In celebration of National Photography Month, we sauntered down to the studios of the three DMA staff photographers—Chad Redmon, Ira Schrank, and Jerry Ward—for their take on the exhibition.

On their own work

Chad: The piece that was in the DMA staff art show last year was a pretty good example of my work: I cut a hole and my arm was reaching through, taking a picture. It was a trompe-l’œil, speculative space. I like to play with your expectations of looking at photographs, something that would obviously not actually happen in real time. People have to take a second look at it, even if I’m standing next to them.

Ira: I shoot landscapes mostly. But I’ve also done environmental portraits. I’ll use backdrops to hide the background, or take the environment out, not quite like Penn; I didn’t try to have one specific look. I often use either paper or fabrics to isolate the things I shoot. To a photographer, it enables you to really look at what it is you are looking at, without letting the world cloud it.

Jerry: I’m a commercial photographer; this is my first museum job. My background is in sports, food, and journalism—mostly ads and billboards. I was a Saints team photographer when I was younger. So if it moves, I can capture it.

On their familiarity with Penn:

Chad: I saw an Irving Penn show at the National Portrait Gallery in D.C. in 1988, when I was a freshman at art school. I saw that show 20 times. I went over and over again. I even bought the book, which was one of the first coffee table books I ever bought, and I still have it to this day.

Ira: I’m really fine art oriented, but of all the commercial photographers, he is my favorite.

On their favorite work in the show

Chad: Willie Mays, jumping up. It looks like he’s flying like Superman. It’s not an often-seen photograph. It’s one of the few actually manipulated. He took a photo from a long way away of Willie Mays in action, cut him out of whatever background he was on, and stuck him on a field of white. It doesn’t look like anything else in the show.

Ira: I don’t really have a favorite. There is so much different work. He is all over. The early work that he’s done, where he is an editorial photographer, I love those. But those are so different. It’s hard to see how he goes from those pictures—like traveling around the South—to how he got to his studio work. I guess his experience of being an artist in New York got him from point A to point B.

Jerry: The lady with the martini (Woman in Dior Hat with Martini (Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn), New York, 1952). It’s really high contrast. And it’s cool how the martini works in the glass. And I like food stuff, since I’ve shot food.

On Penn’s most interesting body of work

Chad: I like the portraits of intellectuals crammed in corners, on scaffolding, and what not. It’s really egalitarian the way he took portraits. He would take that mobile studio to North Africa and take pictures of the locals. It looked basically like the set he would shoot fashion people in in New York. It highlights the differences between the people, but it also highlights the similarities between them. It divorces them from the background to such a degree that you have to see the similarities and differences immediately.

Ira: I love the raw backgrounds, which allow the photographic process to show. His portable studio, in a way, cancels out the environment, and he can just engage in his process. And he took the portable studio everywhere, to South America, Africa.

Jerry: I like the food and the American South section. I’m from New Orleans—so, the old barber shop and the people outside. You still see those signs at home. It’s familiar.

On what’s surprising

Chad: I had never seen any of the early street photography. I don’t like it very much. There’s nothing exceptional about them to me, but seeing them doesn’t take the shine off of the rest of his work. It’s good to know that he grew into his aesthetic, as opposed to just arriving fully realized.

Ira: No surprises. But what makes so many of his pictures work so well is that he isolates them. None of the sets are fancy—sometimes it’s torn-up carpet turned upside down. It’s interesting that in our show, when you turn the corner and enter into that newer, color work, it doesn’t quite work in the same way. To me, there is a big difference between what looked like commercial work and his art, which is what we all respond to. Like that work when you walk in [to the exhibition]. What a spectacular photograph.

Jerry: What’s surprising is that Penn would go out and do it his own way. But a lot of [commercial] photographers buckle under to the art director. It’s pretty obvious that Penn was so great that they let him run free. They didn’t tie him up with an art director. The collaboration looked like this: Penn, and-oh yeah-there is an art director, as opposed to, an art director and-oh yeah-there’s a photographer pushing a button. As a commercial guy, that is really cool.

Thanks, Chad, Ira, and Jerry for your insight! Come celebrate National Photography Month with a visit to the DMA this May.

Andrea Severin Goins is Head of Interpretation at the DMA.