Self-portraits are compelling images because they appear to show us the person behind the artwork, offering us a special peek into who the artist was. We hope that by looking at the self-portrait, we can learn something about the subject. Yet, much like the selfies we post on social media, the artists were presenting themselves how they wished to be seen.

Just as selfies allow our friends and family to feel like they’re sharing in our daily lives, they are ultimately the result of our own conscious decisions, just like a self-portrait. The self-portraits we see in museums are images that exist somewhere between how we see the artist and how the artist wanted us to see him or her.

My upcoming exhibition Multiple Selves: Portraits from Rembrandt to Rivera, opening this weekend in the Museum’s European Galleries on Level 2, focuses on this play between how we want to be seen and how we are seen. The majority of the images are self-portraits, ranging from the 17th to the 20th centuries in a variety of media, including etching, lithography, and drawing.

Just as we use objects and clothing in our selfies to identify ourselves (think college t-shirts to mark us as alums or pictures in front of tourist landmarks to show where we’ve been), artists in these self-portraits use different objects and costumes to help us identify the person we see in the portrait as an artist.

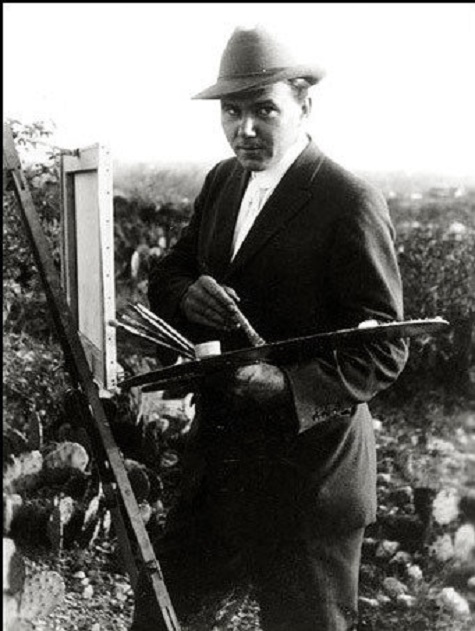

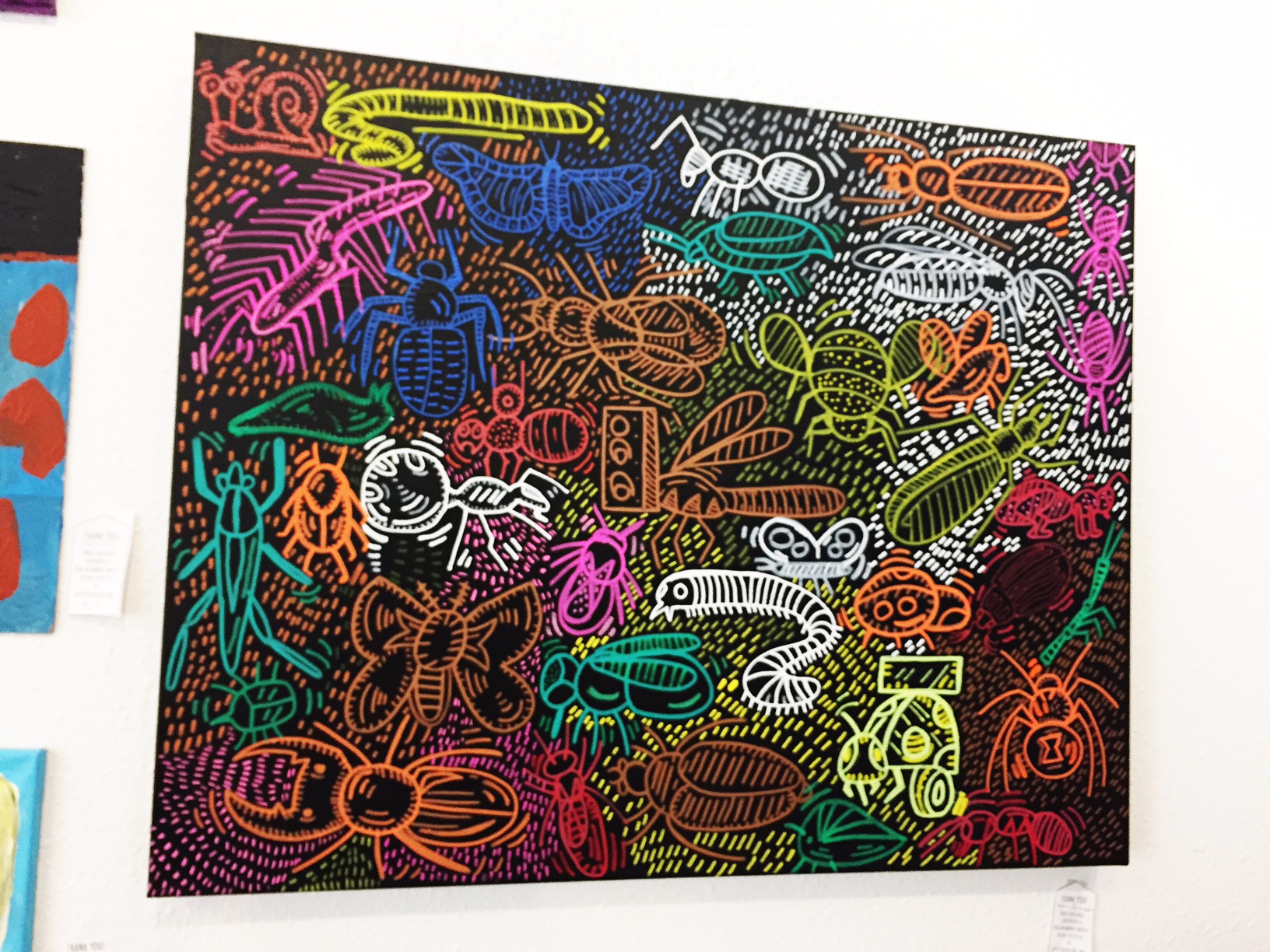

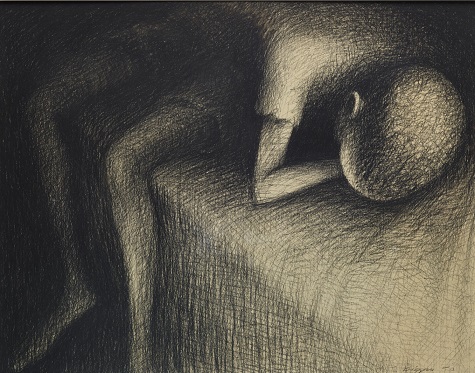

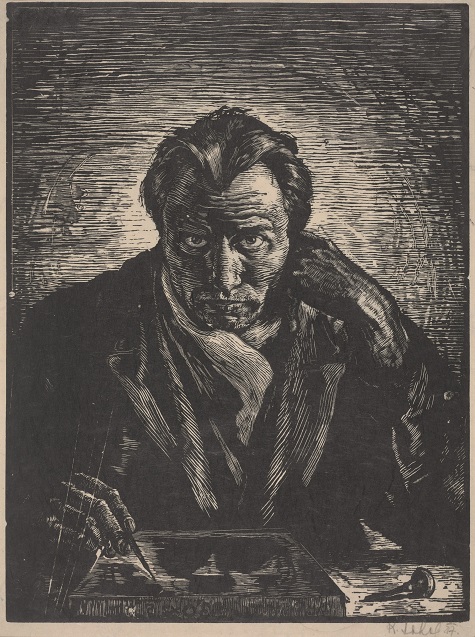

Koloman Sokol, Self-Portrait, mid-20th century, wood engraving, Dallas Museum of Art, anonymous gift, 1949.11

In many of the works, these objects are tools of the trade, or items that are specific to an artist’s working life. This includes palettes, canvases, mahl sticks (used by artists to keep their painting hand steady), drawing implements, and jewelry, which historically marked an artist’s inclusion in a professional guild or within a royal court.

One work in particular offers an intriguing example of this complex dynamic. Self-Portrait by Koloman Sokol is this type of double self-portrait. Sokol, a Slovakian artist by birth who worked extensively in Mexico and the United States, probably created this self-portrait sometime in his 30s. In it, we see not only the completed self-portrait but also the artist caught in the act of creating a self-portrait. At the bottom of the print, the outlines of this second self-portrait take shape. This second self-portrait is being created just as the first one was, through a printmaking process known as wood engraving. To help us identify the work he is doing, he includes his tools—the wood block he is carving on and a burin, a tool used in printmaking to cut into the metal plate or wood block.

In the works that feature artist tools, like Sokol’s, the artists are manipulating their own image to ensure that we as an audience recognize the duality of their self-portrait, that we recognize the artist as an artist through both the self-portrait as a work of art and through the artist’s self-presentation as an artist.

For more about self-portraits, join me for a free Gallery Talk on Wednesday, May 3, at 12:15 p.m. in the exhibition. For another type of double self-portrait, be sure to visit The Two Fridas, now on view in the exhibition México 1900–1950: Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, José Clemente Orozco, and the Avant-Garde, on view only at the DMA.

Amy Wojciechowski is the Dedo and Barron Kidd McDermott Graduate Intern for European Art.