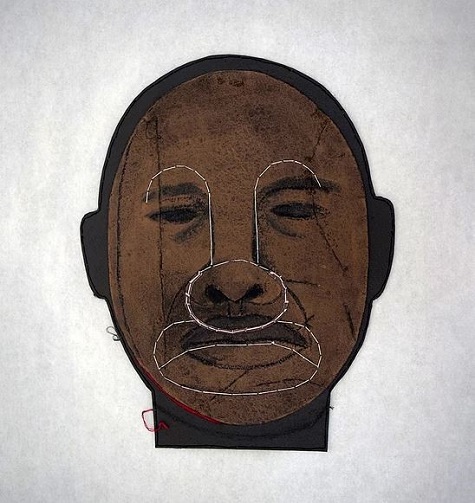

A work by Houston-based Iranian-American artist Soody Sharifi is now on view in the Keir Collection of Islamic Art Gallery. Courtly Love, an archival inkjet print from 2007, is an adaptation of a 15th-century painting in the Keir Collection. The original painting is an illustration of a tale from the Khamsa of Nizami, a collection of five tragic love poems. It depicts a scene from the romance of the Iranian king Khusraw and Armenian princess Shirin. Drunk and guilty of an amorous tryst, Khusraw has arrived at Shirin’s palace on horseback. Shirin, peering out from a window, is counseled by an older woman and refuses him entry. The scene is witnessed by a variety of attendants, including three scribes holding poetic manuscripts below. A darker mood is also present; anxious angels who know the inevitable tragic outcome of the story hover at upper left, while two gardeners with golden shovels foreshadow the twin graves in which the lovers will lie for eternity.

Courtly Love is one of a series of works that Sharifi has termed “Maxiatures,” a play on the term “miniatures” that is commonly used to describe the small format of Islamic book paintings. Sharifi’s works are large. For them, she has selected well-known examples of architectural paintings that illustrate Persian literary classics, such as the Khamsa, to serve as a basis for adaptation through the addition of new figures taken from photography. She also works with the architectural elements in the original image, changing their scale and contents. In this work, some of the original painted figures have vanished, and those that remain become unwitting bystanders to a new cast of figures inserted into the scene: contemporary, young Iranians, mainly women, going about daily tasks. These include making a call at a phone booth, jumping rope, playing with a hula-hoop, painting toenails, installing a satellite dish, and looking over the balustrades and through windows. Three young men speak to the women from outside the garden walls—the circumscribed formalities of courtly love referenced in the title of the work, and perhaps referring to the themes of the original painting.

Sharifi’s work appears to be concerned with issues of dual identities, of a past and present that is especially acute for Iranians of her generation who were exiled by the revolution of 1979. Given that the figures in her works are young, this may represent the nostalgia of young Iranians today who still live in proximity to the elegant palaces and gardens depicted in historical paintings, perhaps inhabited now only by ghosts, like the figures in 15th-century paintings. Her concern with dualities—of language, of national identity, of traditions and contemporary technologies, of political tensions—seems to be present in this work, where contemporaneity hovers over a past that can no longer be reached. Certainly, there is also a sense of humor—it is clever and funny to see modern people in these poetical constructs.

Soody Sharifi’s work is displayed in the Keir Collection Gallery alongside the painting that inspired it so that the public can appreciate her interventions, decode her intentions, and enjoy the presence of both works of art at once. Join Sharifi in person as she shares insights into Courtly Love at our next Late Night on February 15.

Heather Ecker is The Marguerite S. Hoffman and Thomas W. Lentz Curator of Islamic and Medieval Art at the DMA.