Welcome to the introductory blog of the “How it’s Made” series. In this series, I aim to shed some light on the technical methods of how objects in our collection were created and to gather a greater appreciation for art-making in general.

Coming from a metalsmithing background, I wanted to start this series with precious metal objects. I selected Etruscan jewelry because I have such admiration for how beautifully designed and how well-crafted these metal objects are. While studying metalsmithing at the University of North Texas, I had the opportunity to learn several of the same techniques the Etruscans used, but with the convenience of modern tools and technology.

Pair of "a bauletto" type earrings, Etruscan, 6th-early 5th centuries B.C., Museum League Purchase Funds, The Eugene and Margaret McDermott Art Fund, Inc., and Cecil H. and Ida M. Green in honor of Virginia Lucas Nick

Who were the Etruscans?

Early inhabitants of Italy, the Etruscans settled in the northern region of Rome in the late eighth century B.C., and can trace their heritage by name in modern-day Tuscany. The Etruscans succeeded the Villanovan culture, a civilization that established early foreign trade and was adept in creating bronze jewelry. The influx of Greek colonization in Italy aided in the transition from Villanovan to Etruscan culture, which thrived until Roman imperialism succeeded around 200 B.C.

What Makes Etruscan Jewelry Interesting?

Today, it’s no mystery why jewelers love to use gold. Gold is a very easy metal to work with; it’s malleable (which means it’s easy to shape and form), there is less clean up after soldering, and it doesn’t tarnish over time. So, why is Etruscan gold so amazing? This ancient civilization manipulated metals and implemented tedious applications without the modern convenience of a torch and other fancy tools is pretty incredible. It amazes me that such delicate pieces could be fused together by controlling an open flame instead of a pressure-controlled torch.

Take granulation, for example. Granulation derives from the Latin word granum, meaning “grain,” and it describes the method of fusing small granules to a base. This ancient technique is a hallmark of Etruscan jewelry and requires a lot of meticulous preparation.

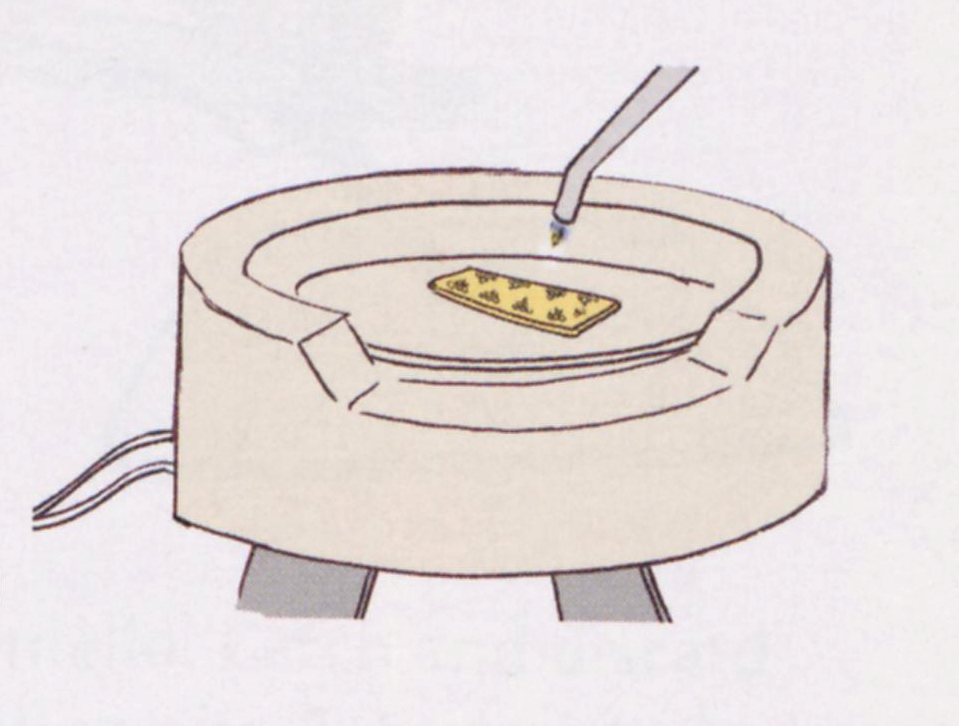

In order to make the granules, Etruscans would place gold dust or very small clippings of metal into a crucible. In order to keep the granules from clumping together and melting into one giant granule, they placed layers of charcoal between the clippings, and then heated them to their melting point. At that point, the metal dust or clipping will roll itself into a little ball and create a granule.

Once you have your tiny granules, you have to then position them and fuse them to a base. Today, metalsmiths use ready-made flux and solder to join granules on a base. According to Jochem Wolters in his essay “The Ancient Craft of Granulation: A Re-Assessment of Established Concepts,” adhesive non-metallic solders such as the gem chrysokolla (which literally translates to “gold glue”) or any other copper-bearing compounds were the solder of choice for the Etruscans.

If you’ve never soldered before, and you’re having a hard time visualizing this, think of a peanut butter sandwich. You have two surfaces that need to be fused together. Think of the base and the granule as the two slices of bread, and the solder as the peanut butter; without it, the two surfaces cannot fuse. Once you have your solder and granules in place, you place your object over an open charcoal fire and heat it evenly. Amazing!

It’s important to note that the Etruscans didn’t reinvent the wheel in terms of metalsmithing techniques, for many of the methods they are recognized for (such as granulation, filigree, chasing, and repoussé) were borrowed from neighboring cultures. The true reason Etruscan jewelry stands out is because of the ancient metalsmiths’ technical skill and amazing ability to manipulate gold with precision. I can attest that even with modern tools, it is difficult to execute many of the techniques that were used in the 6th and 7th centuries B.C.

I hope you find Etruscan jewelry as riveting as I do, and if you have any questions about other works from our collection, please feel free to post your questions in the comments area.

Happy making,

Loryn Leonard

Coordinator of Museum Visits

Resources:

- Barbara Deppert-Lippitz, Ancient Gold Jewelry at the Dallas Museum of Art, (Washington: University of Washington 1996), 31-57.

- Tim McCreight, The Complete Metalsmith: Professional Edition, (Davis Publications: February 2004).

- Jochem Wolters,”The Ancient Craft of Granulation: A Re-Assessment of Established Concepts,” Gold Bulletin, Vol. 14, Number 3, 119-129.