Ed Clark is an American abstract expressionist and pivotal Black artist in the DMA’s collection who experimented with shaped canvases. His large-scale painting Intarsia is on view for free in the exhibition Slip Zone: A New Look at Postwar Abstraction in the Americas and East Asia. To create this work, he laid raw canvas on the floor, poured acrylic paint directly on the surface, and spread it across the canvas with a push broom in a performative process. The title of this painting refers to a knitting and metalworking technique used to create fields of different colors that appear to blend in and out of one another. Combined with the elliptical shape of the canvas, which Clark saw as evocative of the shape of an eye, the radiant colors give the overwhelming sense of an expanding, pulsating image. Find out how our team of art conservators and preparators worked to preserve this work’s thick layers of paint by stretching the canvas before displaying it.

From Laura Hartman, Paintings Conservator at the DMA:

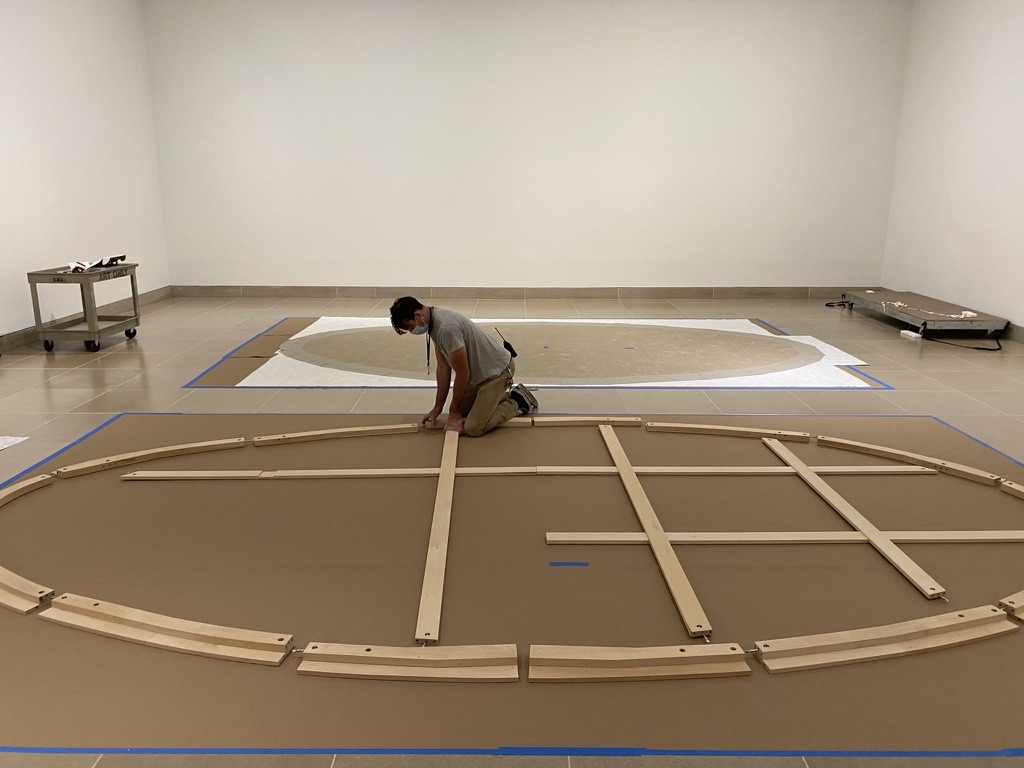

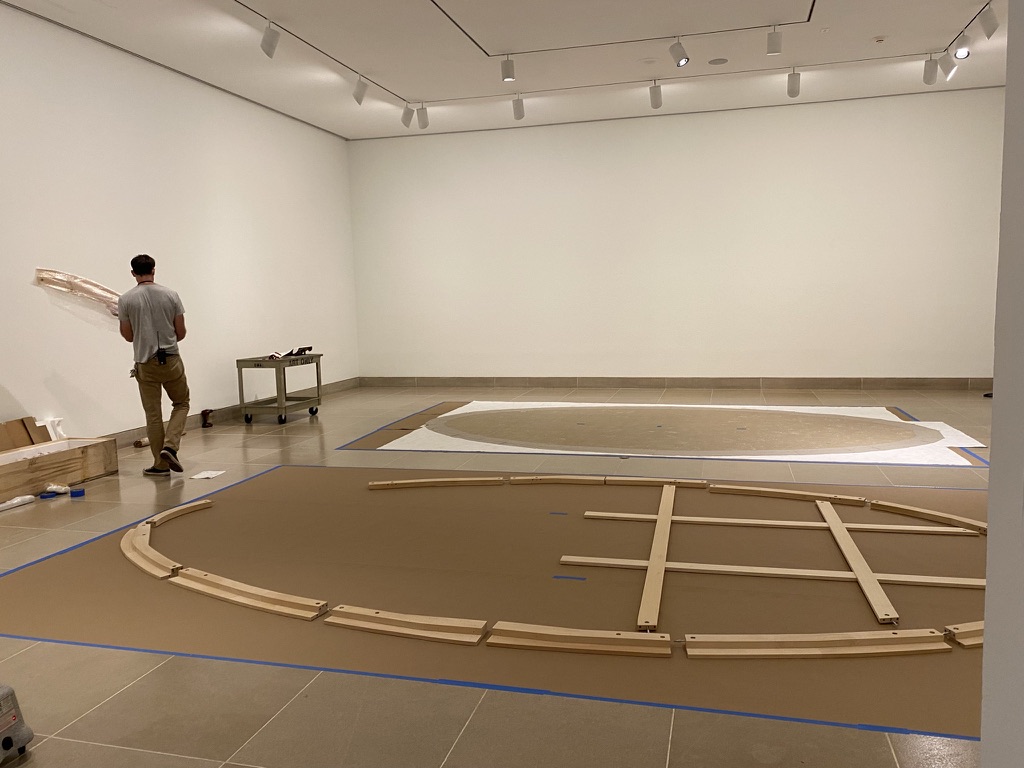

It was a true team effort—the painting measures over 5 meters by 3.5 meters, and weighs over 200 pounds! This painting is unique in that the artist has applied so many layers of paint that the paint is in fact thicker than the canvas, which changes the entire physics of the work. It has also traditionally been shown pinned directly to the wall, which was possible in 1970 when it was painted, but now the work has aged and needs a new approach to ensure longevity.

We worked directly with a stretcher maker in New York to design a stretcher that would hold the weight of the piece while remaining thin, giving the appearance that the work is pinned to the wall.

I worked with our preparators to create edge extensions, or a strip lining, and attach these to the back of the work to be able to stretch it while retaining the illusion of pinning. We first stretched a loose lining, which is a giant piece of canvas that acts as an additional support, and then carefully stretched the work onto the prepared stretcher, slowly increasing tension over several days to allow the paint to relax and release into a comfortable position. The work is now secure for the long haul, while retaining the artist’s original intention.

It took a lot of hands but we got it done! It takes at least 8 people to safely move the work, so all hands were on deck for this one!